Land Hoe! Personal reflections on the subject of returning dignity to hoes and men

My lifelong love of horticulture and career involving urban agriculture has resulted in the fact that I have developed a love of hoes and other implements used to cultivate the earth. You may already be snickering beneath your breath and wondering why on earth a man would use the expression “love of hoes” in a today’s world where the use of the true meaning of the word “hoe” has long been lost to boys and men who have lost their sense of dignity and love for that which is most sacred on earth: our women, our soil, and the basic tools for cultivating our food and our dignity. As boys and men, the language we use to express our sensual ideations has been degraded in the streets, playfields, and locker rooms to terms that achieve the opposite goal of endearing the subjects of our love interests. With sadness, I observe that too many boys and men today have a stronger emotional connection with the word “ho” than “hoe.”

This degradation of terms of endearment has permeated almost every level of American society. I can state this both because I am a man and also leader in the exotic and wild field of cutting edge education known as “garden based learning.” In essence, practitioners in this field use the garden as a classroom to teach life sciences and other subjects that are catalyzed and leveraged by getting children out the box (indoor classrooms) and engage them in their school and community environments in ways that accelerate and stimulate the learning process. We make gardens and learn in them.

I can guarantee you that I can walk into nearly any classroom in America and stand with a hoe in my hand and announce that I am going to give a lesson on the importance and history of hoes and then spend the rest of my time trying to suppress the giggling and laughter that will tend to override any sense of curiosity about REAL HOES, and how important that are to the both the evolution and survival of humanity. I have realized through numerous such experiences that I cannot get to the exciting subject of hoes until I first address the degradation of the vernacular and resulting loss in human dignity that is apparent in the current state wherein one cannot discuss the value and history of one the world’s most important tools for producing food without being laughed out of the room. So, I write this essay to gather my thoughts and prepare myself for the challenge. I reclaim my hoe and male dignity with this essay. You may laugh and giggle, but kindly observe the dis-ease in your body with this laughter, and kindly consider reclaiming a word and a tool that is essential to human life: the hoe.

Let’s get this out of the way right up front: the term “whore” has been abbreviated in the crudest manner to the term “ho”. The expression has become a part of pop-culture and media, and rears its ugly head across all color and class lines. The word “ho” seems ridiculous from a linguistic point of view since the word “whore” was already a one syllable word. On the surface this not only reflects the ugliness and ignorance of the speaker, but also the laziness. Ironically, the term “ho” existed long before in the English language: the word “ho” pronounced “hō” served linguistically as an interjection or exclamation, emerging in the etymology of Middle English in the 15th century as a term used to attract attention to something. A classic example, and often reiterated in old black and white movies is inspired by the literature, such as the 1620 documentary work of “Land Ho!: A Seaman’s Story of the Mayflower, Her Construction, Her Navigation, and Her First Landfall” by W. Sears Nickerson and Delores Bird Carpenter.

Even deeper and more ancient than this nautical reference is the origin of the word in either Old Norse language hó or in Old French language wherein ho is understood to mean “halt”. Meanings such as these are generally lost in the present day use, a mostly American corruption of the word whore, a slang pejorative referring to a sexually loose woman or prostitute. In general use, the term is used as vulgar noun and flung about in the streets and pop culture as a highly offensive term referencing females with connotations of loose sexuality.

I ask us to turn toward land for meaning, to halt the corruption and hijacking of the word “hoe,” a useful and important term for our culture and cultivation, and to reclaim and rejuvenate our sense of meaning with regard to the word and the tool. In contrast to the vulgarization “Ho”, the term “hoe” has entirely different and far more interesting etymological origins. The Old English noun was recorded as early as 1363, referring to a “hoe, mattock, or pick-axe” and is related to the Old English “heawan” “to cut” (see hew). The earliest known use of the verb was recorded in 1430. The term has morphed and taken many turns in the language from the reference to a “Hoe-cake” in 1745 American English, referring to a pastry that was reportedly baked on the broad thin blade of a cotton-field hoe, to the Hoedown, an expression for a “noisy dance,” that was first recorded 1841, perhaps inspired by a group of dance motions commonly found in mundane farm chores.

As a verb, “to hoe” can refer to actions such as cultivating the surface of the soil around plants, to cut, dig, scrape, turn, arrange, or clean, with a hoe; as to hoe the earth in a garden; to pile or move soil up around the base of plants (hilling or berming), to create narrow furrows (drills) and shallow trenches for planting seeds and bulbs, or generally digging and moving soil away from roots or tubers (such as harvesting potatoes or carrots), and to remove or chop weeds, roots and crop residues. Colloquialisms such as “To hoe one’s row” refer to do one’s share of a job or a “tough row to hoe” in reference to a difficult task to carry out.

I could easily write an essay just on the etymology of these words and contrasting the differences and similarities in their meanings. But in this case, I have a tough row to hoe, that is to keep your attention long enough to explore a topic that on the surface seems to have little relevance to an urbanite such as yourself. I presume that you are probably an urbanite, because I imagine that most farmers and country folk might consider this topic a rather mundane one, versus one of urban legend. Regardless of whether you have dirt under your fingernails or not, I want to return to exploring the basic understanding of the hoe as an agricultural implement.

The hoe is a tool that used around the world, evolving from the use of a simple stick and enhanced with a wide variety of bits of metal, (and in earlier human history with bone or stone). Many of you are familiar with the common hoe, usually a long handled tool with a flat blade of various shapes, primarily used for weeding and for breaking up the soil. After the use of sticks, it was most likely among the first agricultural implements in recorded history. The earliest hoes were bent or forked sticks. Flaked-stone implements were used in Mesopotamia in the 5th millennium BC. Archeologists have found evidence of these tools along with flint-bladed sickles and grinding stones and other evidence associated with farming settlements. Hoe blades were made a variety of objects found in nature, including animal horns, bones, and seashells.

Over the course of history, in all corners of the planet, we can find variations on the hoe, such as the pick, the adz, and the plow. The two basic parts of the hoe, the stick (handle) and the head (blade) have evolved over time, and progressed from bone/stone/shell to copper, bronze, iron, and steel. Modern hoes, as in ancient times, are dragged or thrust.

Farmers and gardeners today use a wide variety of hoes that can readily be identified on the internet: American hoe, adze, asadon, bachi gata hoe, burgeon and ball hoe, grape hoe, eye hoe, circle hoe, hula hoe, collinear hoe, diamond push-pull hoe, gooseneck hoe, half moon hoe, ibis hoe, plow hoe, scuffle-neck hoe, swan neck hoe, trapezoid hoe, warren hoe and the list goes on and on. There is a hoe for every purpose, for chopping, scrapping, cultivating, shaping, aerating, harvesting, and more. There are museums around the world that feature hoes, companies that specialize in hoes, instructional materials on how to hoe, histories of hoes, international hoes, culturally specific hoes, mechanical hoes, even metaphorical poetic hoes.

Jembe (Hoe)

A hoe as we know it, with its sturdy handle, is a hoe that has no fear of grass.

And those who say this isn’t so don’t belong with us.

The hoe doesn’t fear grass; that’s been its nature for ages.

When it enters the garden, the hoe clears it at once, digging up all the grass – with no light touch.

Put it into the weeding, and you’ll see I’m not guessing.

The hoe doesn’t fear grass; that’s been its nature for ages.

It relishes cutting down the bushes and the toughest reeds.

It has no fear or inhibitions: it chops and slashes the grass and asks no questions.

It’s not pushed around in its tasks, no matter where it goes.

The hoe doesn’t fear grass; that’s been its nature for ages.

And when the hoe doesn’t work, you can be sure someone has erred.

Maybe the problem is malice, or confusion about method.

It’s thrown away in a grassy field, and there’s no one to raise objection.

The hoe doesn’t fear grass; that’s been its nature for ages.

-Mwinyihatibu, 1977. Mwinyihatibu Mohamed (born 1920), a resident of Tanga on the Tanzanian coast, is a Swahili poet who composes traditional free verse poetry that elaborates with metaphors that advise and contrast meanings that encourage an audience to think about simple things such as a spider, a needle, a puddle or a hoe, but also making a point about relations in the human world.

In 1899 an American schoolteacher, Charles Edward Anson Markham (1852-1940), who used the pen-name Edwin Markham, was inspired by an 1863 painting to write a poem. The painting was “L’homme à la houe” (above) by the French artist, Jean-François Millet (1814-1875); the poem was “The Man with a Hoe.”

“L’homme à la houe”

The Man with a Hoe

Bowed by the weight of centuries he leans

Upon his hoe and gazes on the ground,

The emptiness of ages in his face,

And on his back, the burden of the world.

Who made him dead to rapture and despair,

A thing that grieves not and that never hopes,

Stolid and stunned, a brother to the ox?

Who loosened and let down this brutal jaw?

Whose was the hand that slanted back this brow?

Whose breath blew out the light within this brain?

Is this the Thing the Lord God made and gave

To have dominion over sea and land;

To trace the stars and search the heavens for power;

To feel the passion of Eternity?

Is this the dream He dreamed who shaped the suns

And marked their ways upon the ancient deep?

Down all the caverns of Hell to their last gulf

There is no shape more terrible than this–

More tongued with cries against the world’s blind greed–

More filled with signs and portents for the soul–

More packed with danger to the universe.

What gulfs between him and the seraphim!

Slave of the wheel of labor, what to him

Are Plato and the swing of the Pleiades?

What the long reaches of the peaks of song,

The rift of dawn, the reddening of the rose?

Through this dread shape the suffering ages look;

Time’s tragedy is in that aching stoop;

Through this dread shape humanity betrayed,

Plundered, profaned and disinherited,

Cries protest to the Powers that made the world,

A protest that is also prophecy.

O masters, lords and rulers in all lands,

Is this the handiwork you give to God,

This monstrous thing distorted and soul-quenched?

How will you ever straighten up this shape;

Touch it again with immortality;

Give back the upward looking and the light;

Rebuild in it the music and the dream;

Make right the immemorial infamies,

Perfidious wrongs, immedicable woes?

O masters, lords and rulers in all lands,

How will the future reckon with this Man?

How answer his brute question in that hour

When whirlwinds of rebellion shake all shores?

How will it be with kingdoms and with kings–

With those who shaped him to the thing he is–

When this dumb Terror shall rise to judge the world,

After the silence of the centuries?

-Jean-François Millet (1814-1875)

The poem became as famous as the painting. Both of these creative works serve as testimonies to the burdens that humans heap upon the human race or the burdens we place upon ourselves. What I see in the visual and poetic metaphors presented here is the opportunity to see the hoe as something that can hold us up and be a tool for recapturing our dignity, even in the face of the worst insults we can manage to hurl upon ourselves or upon our fellow human beings.

There’s an old children’s saying, “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words can never hurt me.” This is a fable that needs closer examination. Words can hurt more than sticks and stones…they can break hearts, devastate lives, wound the soul, ruin reputations, destroy relationships, even kill. Words can hurt with blunt, cruel force. Cruel and hateful words such as “ho” are verbal abuse that can cause long lasting emotional damage. When someone hurts us, the memories return to us over and over and can live with us forever. There may be words from your childhood that you still haven’t escaped. Weirdo. Stupid. Fatso. Ugly. Lazy. Crybaby. Dummy. Loser. Moron. Sissy. Chicken. And now “Ho.” These painful words can be hurled when we are young as short and shallow barbs, but as we grow, these hurtful words can hook deeper and deeper into us and grow into phrases, paragraphs, and even narratives that we can internalize and propagate. If we don’t find a way to heal from them, they can cause lasting, permanent damage. Of course, many grown-ups use these words. But one must question whether “adults” who choose such words have really matured. These ugly words are can be like cancers in the soul and in the culture. As I chop away with my hoe, I stare into the earth and the rhythm gives way to healing, I turn toward the land for meaning, the hoe meets the earth, I swing and chop and pull, and I halt the corruption in my soul, the words give way to sweat, the sweat mixes with the soil, the soil mixes with my soul, I cultivate my own healing, the hoe is my implement, I am a man with a hoe.

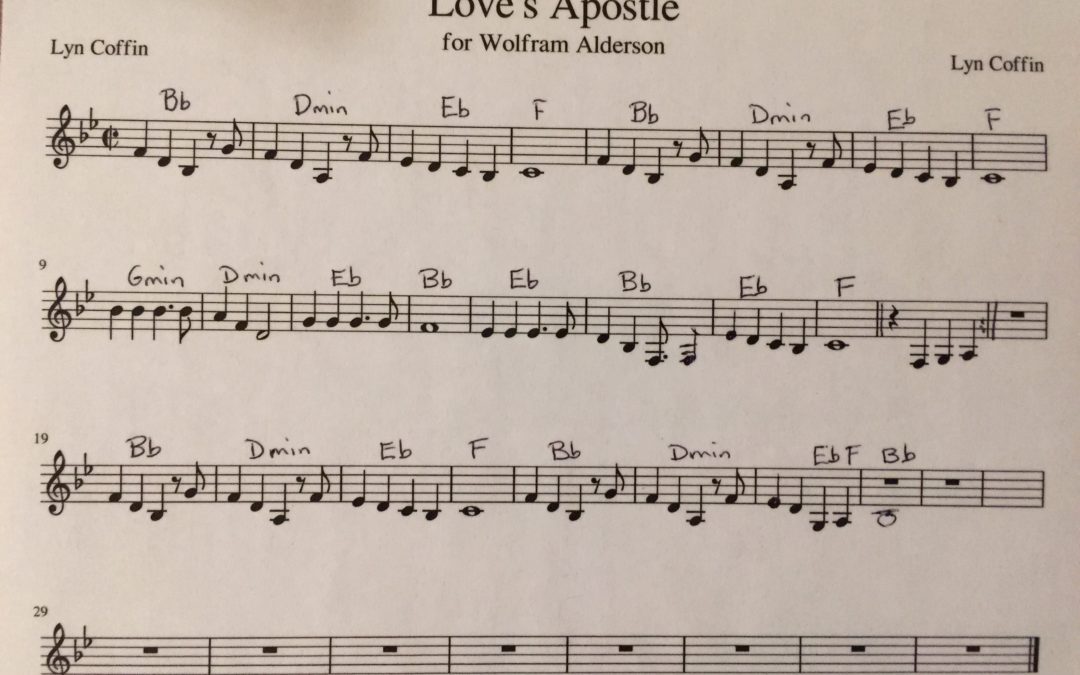

Four decades ago, after leading efforts to organize the first certified farmers’ markets in the inner-city communities of Los Angeles, I began the second phase of food system change work with the Hunger Organizing Team. I developed an urban agriculture program that was about growing food in the inner city. To my good fortune, I became the student of an amazing urban farmer in South Central Los Angeles named Earl Ambeau. He taught me some real farming skills, including how to hoe a row, and some of the specialized knowledge that urban farmers need to know in order to survive in the inner-city. Here is photo of me with Earl back in 1980:

Earl was in heaven when he was in the garden and he planted that seed in me too. When I’m in the garden, I feel like I’m in heaven.

Here is another image of Earl with heaven in his face:

Earl grew a huge variety of butter beans, collard and mustard greens, melons and squash, and he taught me how to use a hoe, among many more other skills. His wife also made the best bean pie I have ever eaten.

Earl welcomed me into his garden and home in South Central Los Angeles, and he helped shape my gardening soul, as well as my urban farming skills. It is hard to put into words the impact he had on me, but his love for urban farming was so deep that it inspired you. When he would hold up one of his home grown beans or squash, there was such incredible pride and joy that you felt like you were in the presence of something magic. I can’t help but think of Earl whenever I have a hoe in my hand. When you pick up a tool, you don’t usually just fall in love with it. Look at Earl in the picture…do you see the love he has for tilling the soil? He imbued that love into the meaning I hold for the hoe.

I want to reclaim this sense of love and respect and meaning with regard to the hoe. I believe that for man and woman alike, we can regain our dignity and bury the erosion of spirit that comes along with linguistic degradations of the word hoe. I see that dignity of the hoe is not merely found in the amazing breadth of functionality that it provides as a tool, nor is it solely contained in an ancient history of noble purpose, but in our common sense of being agents of fertility and creation, of being producers of food, of tilling the earth, of respecting the sacred, of becoming and serving as common implements designed for loving the earth and all of its inhabitants who happen to rely on a very thin layer of dirt called topsoil that feeds and sustains all life on the planet.

-Wolfram Alderson

Heigh-hoe, heigh-hoe,

It’s off to garden we go.

With a bop in our step

And a rhythmic chop,

Heigh-hoe, heigh-hoe, heigh-hoe!

-Anonymous

Earth is here so kind, that just tickle her with a hoe and she laughs with a harvest.

-Jerrold, Douglas William

The cure for this ill is not to sit still, Or frowst with a book by the fire; But to take a large hoe and a shovel also, And dig till you gently perspire.

-Kipling, (Joseph) Rudyard

References and Related Links:

Men Growing Up To Be Boys by Lakshmi Chaudhry

Sources of Hoes

- Burgon & Ball – Sheffield England

- Tramontina

- Clarington Forge

- Rittenhouse Garden Tools

- Wilkinson Sword Garden Tools

- Wolf Garten

- Red Pig Tools

- Sneeboer Gardening Tools

- Spear and Jackson

- Rogue Hoe

- Chillington Tools – Traditional Tools

- EasyDigging.com

- Seymour

This post is recycled from one of my old blog sites.

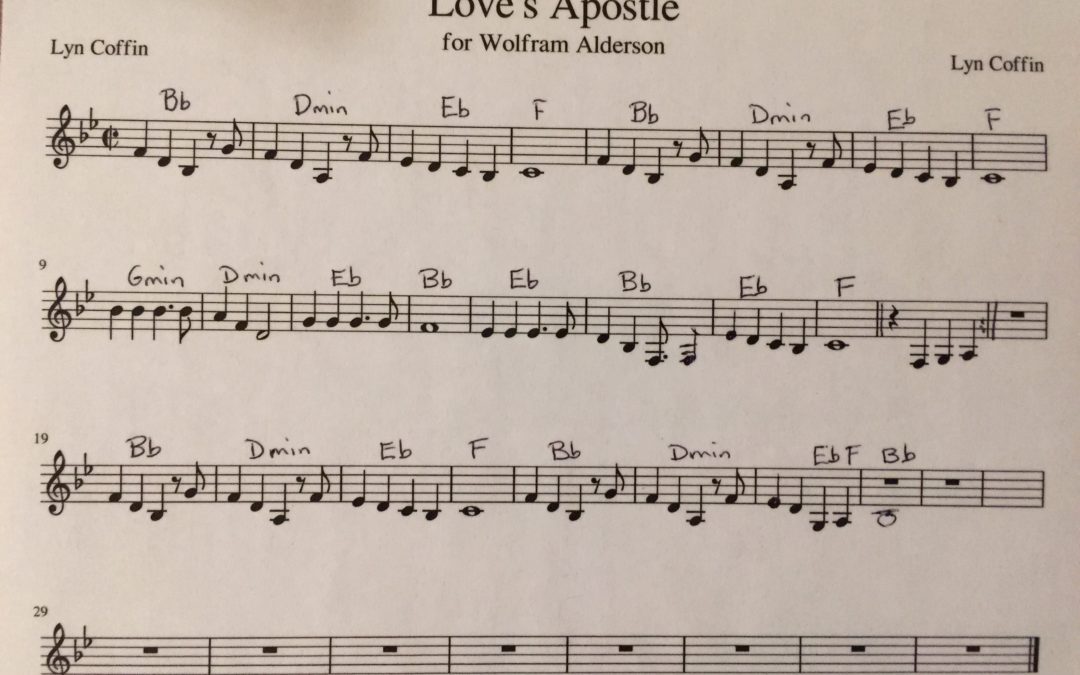

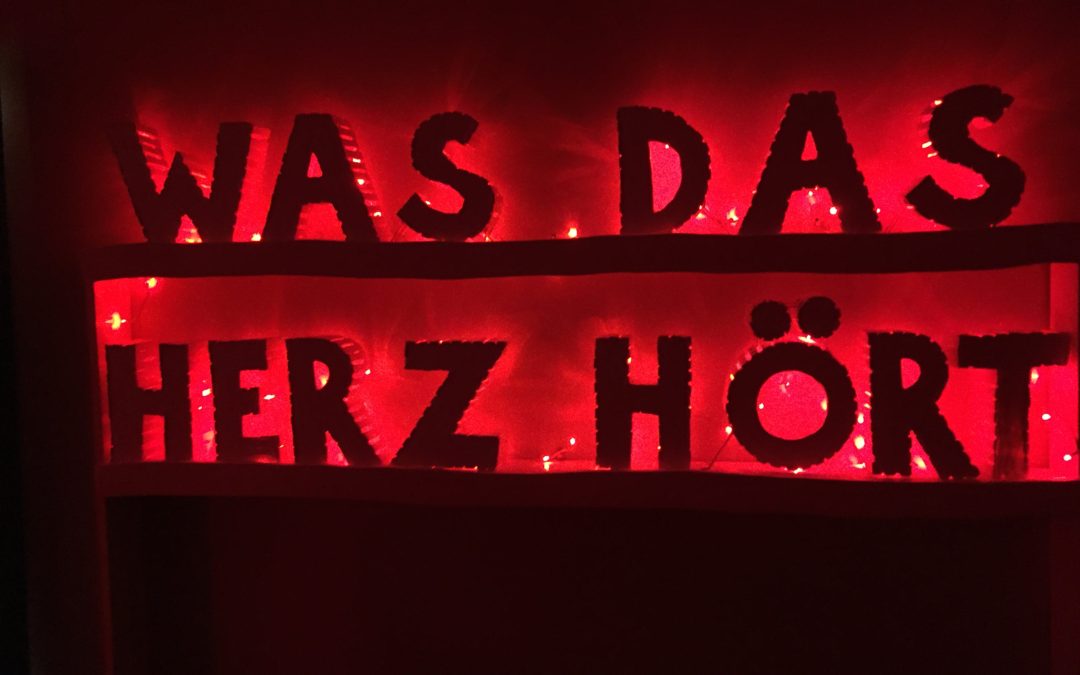

German Connection

Wolfram on Instagram

In The Museum of Primitive Art

“Who said the dead are dead,”

the Thing in the showcase said.

“We are sent here to learn the lessons of toil.

We are sent here to improve the soil.

We are instruments of reality:

experiments in immortality.”

My mother, Cella Coffin, wrote this in 1964. I will share more of her poetry in the future, but this is perhaps the most appropriate poem she wrote for this website. She introduced me to art at very young age, taking me along with her when she modeled for artists like the Soyer brothers in New York City. My earliest memories include the smell of turpentine and oil paints in their studios.

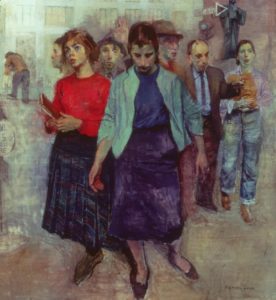

Here is one painting of her (she is wearing the red sweater on the left):

Farewell to Lincoln Square by Raphael Soyer, 1959

Here she is again:

Cella in Red by Rafael Soyer

I love this poem because it not only speaks to art, but also the soil. I have a long background in horticulture therapy and urban agriculture, and these parts of my life aren’t separate, but part of a continuum – and they show up here in the same poem! Without my mother’s encouragement, I never would have imagined a life as an artist. She struggled her whole life to publish her poetry, and at one time papered a whole wall with rejection notices from publications that had turned her down. That didn’t stop her – she just wore it as a badge of honor. For most of my life, I placed my art on the back burner like my mother – she had to raise three children and poetry was a luxury for her. I’m honoring my mother’s work, and fulfilling a dream we both shared – to put our art on the front burner!

Recent Comments